History of Tawi-Tawi, Its Culture, and the Legacy of the Bangsamoro

Introduction

The history of Tawi-Tawi is a story of resilience, maritime heritage, and cultural identity that stretches across centuries of Southeast Asian development. As the southernmost province of the Philippines, Tawi-Tawi is more than just a geographical frontier. It has been a crossroads of civilizations, trade, and religion, serving as a bridge between the Philippines, Borneo, and the wider Islamic world. Over generations, its communities developed a strong sense of identity shaped by continuous exchanges with merchants, seafarers, and travelers who passed through the region. These interactions helped form a rich cultural environment that continues to define daily life in the province.

Known for its rich maritime traditions, Sama-Bajau culture, Tausug heritage, and Islamic roots, the province holds a central place in the historical narrative of the Bangsamoro people. This province history timeline reveals the spread of Islam in the archipelago, the rise of the Sultanate of Sulu, resistance against Spanish colonizers, the challenges of American and Japanese occupation, and its eventual recognition as an independent province in 1973 through Presidential Decree No. 302.

Understanding the historical significance of Tawi-Tawi is crucial not only for appreciating the identity of its people but also for recognizing its role in Southeast Asian history. From being a maritime trade hub to becoming a frontline of anti-colonial resistance, Southern Philippines embodies the resilience of the Bangsamoro people and their deep-rooted connection to Islam and the sea. Today, the province remains a living archive of traditions that survived centuries of change and continue to guide its communities.

Pre-Islamic Tawi-Tawi

A Maritime Crossroads

Austronesian Settlers in Tawi-Tawi

Long before Islam arrived, the islands of pre-Islamic Tawi-Tawi were inhabited by Austronesian settlers who migrated across the seas thousands of years ago. These settlers were the ancestors of today’s Sama-Bajau culture in Tawi-Tawi and the Tausug people. Known for their advanced boat-building techniques and seafaring skills, the early settlers thrived in coastal settlements, living in stilt houses and outrigger boats. Their daily lives were centered on fishing, crafting tools, and navigating the waters that linked different communities across the archipelago.

The Sama Dilaut sea nomads, often referred to as the gypsies of the sea, embody this ancient heritage. Their mobile lifestyle revolved around fishing, pearl diving, and boat-making, with the sea as their central lifeline. Unlike agricultural societies in northern Philippines, the people of Tawi-Tawi cultivated a flexible maritime culture that allowed them to maintain connections across the Sulu Archipelago and beyond. Their inter-island voyages also enabled regular exchanges with neighboring communities, which helped spread stories, songs, and rituals that strengthened their cultural identity.

Maritime Trade in the Sulu Archipelago

By the tenth to twelfth centuries, the province history timeline already intersected with broader maritime trade in the Sulu Archipelago. Archaeological evidence, such as Chinese ceramics, beads, and ironware, demonstrates active commerce with Chinese, Arab, and Bornean traders. These international exchanges influenced local craftsmanship, introduced new materials, and widened the economic opportunities of the islanders.

Local products like pearls, trepang, and shark fins were exported in exchange for silk, porcelain, and beads. These exchanges made Tawi-Tawi an early participant in the regional economy, embedding it into Southeast Asian history even before European colonization. This pre-Islamic cosmopolitanism set the stage for the islanders’ acceptance of a new religion and governance system in the late fourteenth century. As new ideas traveled through trade routes, Tawi-Tawi became more open to cultural transformation, which would later help Islam spread quickly and meaningfully.

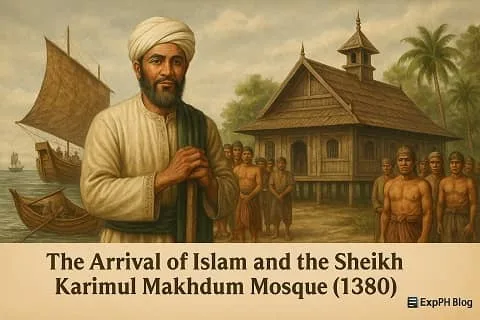

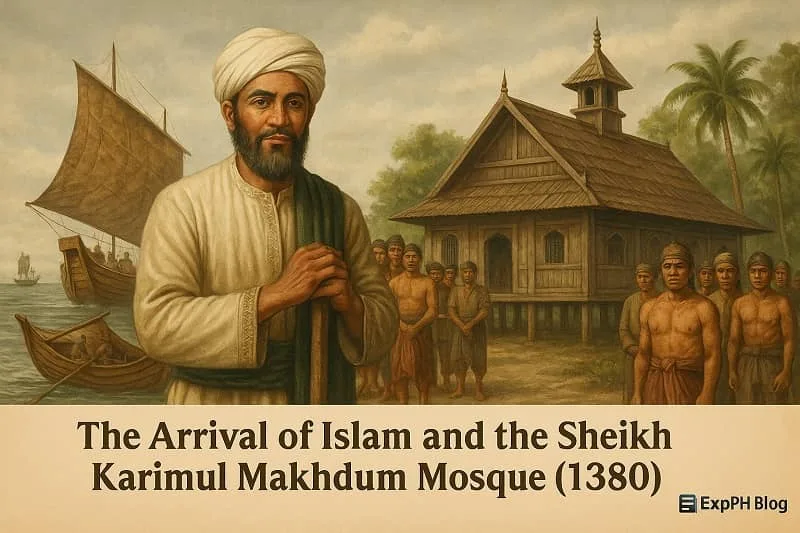

The Arrival of Islam and the Sheikh Karimul Makhdum Mosque (1380)

The defining transformation in the history of Tawi-Tawi occurred in 1380, when Sheikh Karimul Makhdum, an Arab-Malay missionary, landed on Simunul Island. He introduced Islam and built the Sheikh Karimul Makhdum Mosque, widely regarded as the first mosque in the Philippines and among the oldest in Southeast Asia. His arrival introduced a spiritual framework that offered ethical guidance, unity, and a greater sense of community responsibility.

Though the original wooden mosque has long since decayed, four wooden pillars remain preserved within the modern structure. Today, the mosque stands as both a National Historical Landmark and a National Cultural Treasure. Pilgrims continue to visit this site as a reminder of the beginning of Islam in the Philippine islands.

The arrival of Islam reshaped the Bangsamoro province identity. It introduced Shari’ah-inspired governance, encouraged the growth of Islamic education through madrasahs, and connected the islanders to the Islamic centers of Brunei, Malacca, and the Middle East. Quranic recitation, Islamic festivals, and Jawi script began to flourish, weaving Islam into the cultural fabric of the province. This religious shift also strengthened political alliances, supported trade networks, and helped unify diverse communities around a shared belief system.

Integration into the Sultanate of Sulu

Tawi-Tawi’s Role in the Sultanate

By the fifteenth century, Tawi-Tawi became a vital part of the Sultanate of Sulu, founded by Sharif ul Hashim. This powerful Islamic state controlled vast territories, including parts of Mindanao, Palawan, and northern Borneo. The influence of the Sultanate expanded through diplomacy, trade, and maritime strength, shaping the political direction of the region.

Tawi-Tawi’s geographic position made it indispensable to the Sultanate. The islands served as stepping stones linking Jolo to Borneo, while the Sama-Bajau and Tausug heritage in the province contributed significant naval strength. Their warships, such as the lanong and karakoa, secured trade routes and defended the Sultanate against external threats. Their seafaring skills became a key component of the Sultanate’s reputation across Southeast Asia.

Cultural and Political Integration

Integration into the Sultanate reinforced the Islam in Tawi-Tawi narrative. Local rulers administered governance using a combination of Shari’ah law and adat, balancing Islamic principles with indigenous traditions. Tawi-Tawi also became a center for religious learning, sending scholars and traders to connect with Arabia and India.

As a result, the province emerged as a gateway of Islamic culture in the Philippines. This period strengthened cultural unity and paved the way for future resistance against colonial powers that attempted to challenge local autonomy.

Spanish Colonization Attempts and Resistance (16th to 19th Century)

The Spanish arrival in the sixteenth century brought an era of conflict. Determined to expand Catholicism and extend Spanish rule, colonizers launched repeated campaigns against the Sultanate of Sulu and Tawi-Tawi. Their presence disrupted trade routes, threatened local authority, and caused widespread tension.

Spanish Moro Wars in Tawi-Tawi

For more than three hundred years, Spanish Moro wars in Tawi-Tawi shaped the region’s destiny. Moro warriors launched seaborne raids, defended their settlements, and protected their sovereignty with remarkable determination. Their knowledge of the seas and coastal routes allowed them to resist Spanish forces more effectively than many other communities in the Philippines.

Despite multiple expeditions, Spain never fully conquered Tawi-Tawi. The 1878 Treaty of Peace and Friendship recognized Spanish sovereignty, but real authority remained in the hands of the Sultan and local leaders.

Preservation of Islamic Identity

Unlike Luzon and the Visayas, Catholicism never penetrated Tawi-Tawi. The province preserved its Islamic heritage, strengthening its identity as part of the Bangsamoro struggle against colonial domination. This preservation later empowered the region’s leaders to advocate for greater autonomy in the modern era.

American Colonial Period and the Moro Province (1898 to 1914)

Moro Province Administration

Following Spain’s defeat in the Spanish American War of 1898, the Philippines, including Tawi-Tawi, was ceded to the United States through the Treaty of Paris. Under American administration, new infrastructure and institutions were introduced, but these often conflicted with traditional practices and community leadership structures.

Moro Resistance

Although large-scale uprisings were less common than in Mindanao, Tawi-Tawi communities continued resisting American governance. Elders shared stories of fighters who defended cultural traditions and local authority. These memories form an important part of Tawi-Tawi’s heritage and strengthen its connection to the wider Bangsamoro struggle.

Japanese Occupation During World War II (1942 to 1945)

World War II brought new hardships to the people of Tawi-Tawi. The Japanese Imperial Army established bases on the islands and imposed harsh conditions, including forced labor and restrictions on movement. Despite these challenges, Moro fighters organized guerrilla resistance and coordinated with Allied forces when possible.

By 1945, the islands were liberated, but the occupation left long lasting scars on families and communities.

Post Independence Period and Separation from Sulu (1946 to 1973)

After Philippine independence in 1946, Tawi-Tawi was still part of Sulu Province. Distance, cultural differences, and a lack of services fueled calls for self governance. Community leaders advocated for direct representation and programs tailored to the province’s needs.

Creation of Tawi-Tawi Province 1973

These efforts culminated in 1973, when President Ferdinand Marcos signed Presidential Decree No. 302, officially creating the Province of Tawi-Tawi. This recognition allowed the province to establish its own government and focus on development suited to its island geography. It also strengthened the cultural and political identity of the region during a period of growing autonomy movements across the Bangsamoro homeland.

Contemporary Historical Significance

Today, Tawi-Tawi is celebrated for its natural beauty, Islamic heritage, and cultural diversity. The Sheikh Karimul Makhdum Mosque continues to attract pilgrims and visitors who seek to understand the beginnings of Islam in the Philippines.

The Sama-Bajau sea nomads and Tausug communities continue practicing their traditions, which include boat-making, fishing, weaving, and performing cultural dances. The province is also becoming known for eco tourism, with its pristine waters, coral reefs, and unique marine life attracting visitors from the Philippines and beyond. Yet, beyond tourism, Tawi-Tawi’s greatest legacy remains its people, who have preserved a culture that survived centuries of political and social change.

Conclusion

The history of the province is a powerful narrative of survival, faith, and cultural pride. From its role in pre-Islamic Tawi-Tawi as a maritime hub to its integration into the Sultanate of Sulu, from centuries of colonial resistance to its establishment as a province, Tawi-Tawi exemplifies resilience.

To study the Southern Philippines history timeline is to understand not just one province, but the enduring struggle of the Bangsamoro to preserve their faith, culture, and identity within the Philippine nation and the wider Southeast Asian region.

Access more guides through the links below.

- Panampangan Island The Hidden Paradise of Tawi-Tawi

- The Majestic Bud Bongao

- The Influence of Islam in Mindanao’s Culture

- Tausug History in the Philippines

- The History of the Sultan of Sulu

- The Southernmost Island Province in the Philippines

10 FAQs about History of Tawi-Tawi

1. What is the historical significance of Tawi-Tawi in the Philippines?

Tawi-Tawi is significant because it is the earliest known entry point of Islam in the Philippines and a central part of the Sultanate of Sulu, shaping the cultural and religious identity of the Bangsamoro people.

2. When did Islam first arrive in Tawi-Tawi?

Islam arrived in Tawi-Tawi in 1380 through Sheikh Karimul Makhdum, who built the first mosque in the Philippines on Simunul Island.

3. Why is the Sheikh Karimul Makhdum Mosque important?

The mosque is important because it is the oldest mosque in the Philippines. Its four surviving wooden pillars symbolize the beginning of Islamic faith in the country.

4. What was Tawi-Tawi like before the arrival of Islam?

Before Islam, Tawi-Tawi was home to Austronesian settlers, mainly the ancestors of the Sama-Bajau and Tausug. These communities lived through maritime trade, fishing, and boat building.

5. How did Tawi-Tawi become part of the Sultanate of Sulu?

Tawi-Tawi became part of the Sultanate of Sulu by the fifteenth century, serving as a strategic maritime base that helped connect Jolo to Borneo and expanded the political influence of the Sultanate.

6. Did the Spanish colonize Tawi-Tawi?

Spain never fully colonized Tawi-Tawi. Despite several military campaigns, strong Moro resistance and challenging terrain prevented Spanish control over the islands.

7. What happened in Tawi-Tawi during the American colonial period?

Under American rule, Tawi-Tawi was incorporated into the Moro Province. New infrastructure and schools were introduced, but local communities resisted policies that conflicted with their traditions.

8. How did World War II affect Tawi-Tawi?

During World War II, the Japanese occupied Tawi-Tawi and established military bases. The locals experienced forced labor and hardship, yet many joined guerrilla resistance efforts.

9. When did Tawi-Tawi become an official province?

Tawi-Tawi officially became a separate province in 1973 through Presidential Decree No. 302, allowing it to establish its own government and development programs.

10. Why is Tawi-Tawi important today?

Tawi-Tawi is important today because of its cultural diversity, Islamic heritage, and growing eco tourism. It remains one of the most historically rich and culturally significant provinces in Southern Philippines.

Test your knowledge about History of Tawi-Tawi, Its Culture, and the Legacy of the Bangsamoro.

This short quiz will help you understand the roots, culture, and historical significance of the southernmost province of the Philippines. Choose the best answer and see how much you already know.

Results

#1. What year did Islam arrive in Tawi-Tawi?

#2. Who brought Islam to Tawi-Tawi?

#3. Where was the first mosque built?

#4. Which group are sea nomads?

#5. What powered early trade?

#6. What empire absorbed Tawi-Tawi?

#7. Who resisted colonizers?

#8. When became Tawi-Tawi a province?

#9. What document created the province?

#10. What is Tawi-Tawi known for?

We appreciate your time and interest in Philippine history and culture.

Please comment your experience with us so we can keep improving and creating better learning tools for you.

A Filipino web developer with a background in Computer Engineering. The founder of ExpPH Blog, running a Philippines-focused platform that shares insights on careers, freelancing, travel, and lifestyle. Passionate about helping Filipinos grow, he writes and curates stories that educate, connect, and inspire readers nationwide.